In their review of sound studies’ evolution over recent decades, SpokenWeb project members Jason Camlot and Katherine McLeod have identified sound as not just a supplementary attribute of poetry and other literary forms, but as a fundamental element in comprehending literary works.1 Sound studies, they argue, not only illuminates the structure and aesthetics of literary texts but also showcases how these works interact with their social and cultural contexts.2 Building on this foundation, Michael O’Driscoll and Kristen Smith delve deeper into the relationship between recordings and printed materials, posing the question, “What remains on the record, and what stays off?”3 Recordings from the Poet & Critic ’69 Conference capture many moments not found in published poetry collections or autobiographies, offering valuable insights that “encourage research into the theories and contexts of literary production, transmission, reception, circulation, and community.”4

Earle Birney’s Lecture and the Anti-Conference

An illustrative example can be found in Earle Birney’s lecture titled “Poetry and Media Mixing,” delivered at the University of Alberta’s Students’ Union Building (SUB) in the Poet & Critic Conference.5 In this lecture, Birney traces the interplay of poetry with various media, including sound and images, starting from the musical notation on medieval manuscripts (00:00:00-00:01:59). He explores the contributions of Dadaist Kurt Schwitters and modernist poet E. E. Cummings to sound poems (00:02:42-00:05:21), and discusses his own experiments with concrete poems (beginning at 00:11:06). This recording not only reveals the historical background and influences of some of the most active advocates of the global concrete poem movement in the 1960s, such as Birney, bill bissett, and bpNichol, but also highlights their collaboration with British poet Bob Cobbing (00:09:14-00:10:13), further demonstrating the movement’s international impact and interaction.

Interestingly, in the recording Birney mentions another poet, Stephen Scobie, who was at the time holding a concrete poem exhibition at the SUB Art Gallery(00:23:28-00:24:13). This information actually reflects a concurrent gathering with Poet & Critic ’69. Scobie’s exhibition was part of the “Anti-Conference,” also organized by the English Department. While Poet & Critic ’69 gathered many of the most renowned Canadian poets of the time, this Anti-Conference aimed to be anti-establishment by providing a platform for unknown poets and students to showcase their art. In his article for The Montreal Star, John Richmond wrote that the Anti-Conference, which received enthusiastic participation from students and the public, was suggested by two organizers of Poet & Critic ’69, Richard Harrison and Rudy Wiebe.6 Richmond described it as “reminding one of tales of the FBI sponsoring left-wing organizations.”7

Regardless of the intent behind this strategy, the Anti-Conference indeed provided an opportunity for young poets and students at the University of Alberta to interact and even collaborate with established poets. The Gateway, U of A’s official student newspaper, reported that the Anti-Conference featured anonymous poetry readings, interpretation of poems through dance and drama, and “an extension” of Scobie’s exhibition through body painting.8 The mixed arts presented at the Anti-Conference resonate with Birney’s lecture on mixed media, highlighting the impact of media advancements in the 1960s, including the proliferation of television and innovations in recording technology, on literature and the arts.

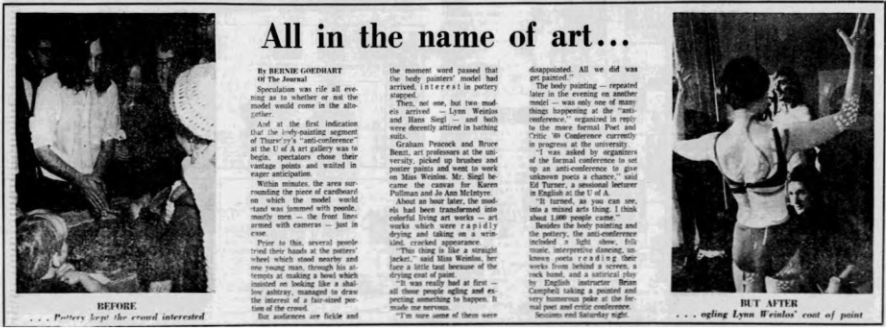

Fig. 1. A news article describing the Anti-Conference. “All in the Name of Art….” Edmonton Journal (1911-), Nov 21, 1969, p. 29.

On the first day of the official conference, a round table entitled “The New Scene in English-Canadian Poetry” hosted a spirited and contentious discussion between three generations of Canadian poets: including Eli Mandel, Margaret Atwood, and bill bissett. Henry Kreisel humorously introduced the three panelists, remarking on the significantly narrowed generational gap in poetry. He noted that Margaret Atwood, born in 1939 and awarded the Governor General’s Prize in 1966, could be seen as Mandel’s figurative daughter and metaphorically, the mother of her contemporary, yet less renowned peer, bill bissett (00:00:00-00:04:30).

The discussion kicked off with Mandel classifying Canadian poets into “hallucinated poets” and “genteel poets” (00:05:02-00:05:18). According to Mandel, hallucinated poets like bill bissett produce poetry filled with passion, madness, and distortion; whereas genteel poets tend to shy away from the most intense and painful human experiences, opting for a gentler, more reality-evasive poetry; Mandel posited that both poetic styles are “the result of a desperate failure in our time” (00:05:19-00:07:40).

Atwood responded by suggesting that some poets Mandel mentioned actually explored both poetic styles (00:07:41-00:07:53). She then questioned Mandel about the characteristics of poetry prior to this divide, if, as he claimed, the divide was a recent development (00:08:36-00:08:50). Mandel explained that earlier poetry tried to “contain the whole universe” through language, while current poetic forms emerged because “words have begun to fail us” (00:08:58-00:09:31). He argued that in 1969, the year humans first landed on the moon, traditional and romantic lines like John Keats’s “Bright star, would I were steadfast as thou art” were no longer suitable for capturing and reflecting modern human experiences (00:09:58-00:10:16). bissett abruptly interjected, asserting that the moon landing was a hoax (00:10:18), which prompted laughter from the audience.

Despite differences with Mandel over the evolution and relevance of language in modern society, and whether concrete poems indicate a distrust or affection for language, Mandel, as the panel’s most senior and esteemed poet, still recognized the accomplishments of Atwood and bissett. SW165-166 offers a glimpse into a profoundly engaging and constructive debate, a testament to how poets at the time understood their own work in relation to other poets and to society at large.

Conclusion

Poets need not be performing for their speech to have significance. In fact, in the case of Birney’s mention of the Anti-Conference, extra-poetic speech can gesture to different forums in which poetry is performed. It can also, as in the round table, reveal how poets contextualize their own work. These recordings are a reminder of the milieu in which these poets were situated, how they saw themselves and their work, and how they made sense of their surroundings.

At once familiarly conversational and plainly historical, listening to poets’ recorded voices both enhances and complicates how we understand them in the present. When we trouble the boundaries between what’s worth studying and what isn’t—what’s “on the record” and what’s off—the result isn’t only a fuller picture of poetry in history: it’s a more critically-aware view of how we interpret poetry now.

Notes

Fig. 1. A news article describing the anti-Conference. “All in the Name of Art….” Edmonton Journal (1911-), Nov 21, 1969, p. 29.

-

Camlot, Jason, and Katherine McLeod. “Introduction: New Sonic Approaches in Literary Studies.” ESC: English Studies in Canada, vol. 46, no. 2–4, 2020, p. 3. ↩︎

-

Ibid., p. 3. ↩︎

-

Michael O’Driscoll and Kristen Smith curated a panel at ACCUTE24 titled “On and Off the Record: Audiotextual Performance and Cultural Resistance.” This exhibition is an homage to their panel, reflecting its themes. ↩︎

-

Camlot, Jason, and Katherine McLeod. “Introduction: New Sonic Approaches in Literary Studies.” ESC: English Studies in Canada, vol. 46, no. 2–4, 2020, p. 3. ↩︎

-

The recording can be accessed at Aviary: https://ualberta.aviaryplatform.com/r/959c53gk4w?media=242028 ↩︎

-

Richmond, John. “A Congress of Poets.” The Montreal Star, 29 Nov. 1969, p. 3. ↩︎

-

Ibid., p. 3. ↩︎

-

“No Names Released at Anti-Conference.” The Gateway, 14 Nov. 1969, p. 12. ↩︎